At the time of his death in 1977, Terence Rattigan was barely remembered by the theater-going public, yet 30 years earlier he was considered one of Britain's most important playwrights. Geoffrey Wansell's Terence Rattigan is the first critical evaluation of the author since his death and, as such, is a major contribution to theater history. More importantly, because Rattigan and most of his contemporaries are dead, Wansell is able to discuss freely their personal and sexual lives. Carefully documented and elegantly written, this biography adds immeasurably to our understanding of British gay male life and the evolution of a gay artistic sensibility. At the time of his death in 1977, Terence Rattigan was barely remembered by the theater-going public, yet 30 years earlier he was considered one of Britain's most important playwrights. Geoffrey Wansell's Terence Rattigan is the first critical evaluation of the author since his death and, as such, is a major contribution to theater history. More importantly, because Rattigan and most of his contemporaries are dead, Wansell is able to discuss freely their personal and sexual lives. Carefully documented and elegantly written, this biography adds immeasurably to our understanding of British gay male life and the evolution of a gay artistic sensibility.

On May 8, 1956, England's most prosperous playwright attended the premiere of an incendiary play by a brash young newcomer. The play, called ''Look Back in Anger,'' assailed just about everything the established writer represented - and when a reporter asked Terence Rattigan what he thought of it, he replied that its author was saying ''Look, ma, I'm not Terence Rattigan.''

''It was a foolish and conceited remark,'' concedes biographer Geoffrey Wansell, ''and would count against him for almost four decades.'' But there was much truth in it, for the play signaled a sea change in British critical taste. And as John Osborne, the author of ''Look Back in Anger,'' and his fellow young playwrights were applauded for their noisy condemnation of the generation that preceded them, the career and reputation of Terence Rattigan crumpled like an imploded skyscraper.

''Rattigan was suddenly cast aside by the British theater with almost unimaginable brutality,'' Wansell writes. ''First prized for his humanity and craftsmanship ... he was then abruptly and summarily dismissed as dated and irrelevant, period and precious, the creator of plays that only middle-aged maiden aunts could possibly like or admire. It was a monstrous judgment on his delicate, gentle talent, but the stigma lasted for 30 years.''

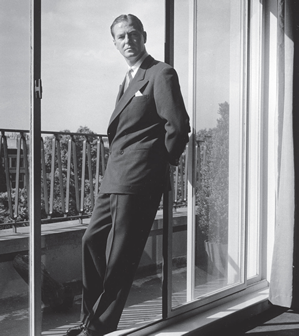

To appreciate the tragedy of Rattigan's decline (and Wansell passionately argues that it was nothing less than tragic), we must appreciate the extent of his achievement. On that day in 1956, a month shy of his 45th birthday, Terence Rattigan was one of the most successful English playwrights in history - his work applauded by critics and audiences, his wardrobe, cars and parties catalogued in the popular press.

From the light comedy ''French Without Tears'' in 1936 to the poignant double bill ''Separate Tables'' 20 years later, he captivated critics and audiences with a string of gold-plated hits - ''Where the Sun Shines,'' ''Love in Idleness'' (retitled ''O Mistress Mine'' in America), ''The Winslow Boy,'' ''The Browning Version,'' ''The Deep Blue Sea.'' For nearly five straight years in the 1940s, three adjacent theaters in London's West End were occupied by Rattigan successes.

The plays, for the most part, were gentle, sympathetic, often witty studies of middle-class men and women in emotional distress - decent people caught up in intense relationships (triangles, father-son conflicts) in which emotions and passions were decisively sublimated. Rattigan's themes, Wansell sums up, were intensely personal ones - ''the illogicality of love, the conflict between heavenly and earthly love, the pain of loss of promise, the defeat of greatness by human foible.''

But these and other motifs remained beneath the surface of his work, to be apprehended through skillfully crafted story and carefully observed character. ''From Aeschylus to Tennessee Williams,'' Rattigan rashly wrote in 1950, ''the only theater that has ever mattered is the theater of character and narrative. ... I don't think that ideas, per se, social, political or moral, have a very important place in the theater. They definitely take third place to character and narrative, anyway.'' But these and other motifs remained beneath the surface of his work, to be apprehended through skillfully crafted story and carefully observed character. ''From Aeschylus to Tennessee Williams,'' Rattigan rashly wrote in 1950, ''the only theater that has ever mattered is the theater of character and narrative. ... I don't think that ideas, per se, social, political or moral, have a very important place in the theater. They definitely take third place to character and narrative, anyway.''

That declaration, like his quip at the premiere of ''Look Back in Anger,'' did Rattigan's reputation no good. ''Already suspect for the flamboyance of his lifestyle,'' Wansell writes, ''he could now be dismissed as facile and unthinking, a man who dismissed ideas and was interested only in commercial success.''

Three years later, in the introduction to his first volumes of collected plays, Rattigan further armed his critics by creating a prototypical playgoer, Aunt Edna, whom no playwright could afford to ignore - ''a nice, respectable, middle-class, middle-aged maiden lady with time on her hands and the money to help her pass it.'' In attempting to advance his long-held belief that theater should be responsive to its audience, he seemed to brand himself a shameless panderer.

Wansell's revisionist biography, the first to make use of the Rattigan papers in the British Library, is brisk, thorough, efficiently organized (except for glossing over the plots of plays that few of his readers will have seen or read), and consistently attentive to the experiences and relationships that shaped both the man and the writer. Like many of his characters, Rattigan ''lived a life of disguise and concealment,'' presenting himself to the world as urbane and assured while privately suffering a pervasive fear of failure, a feeling that his early success was a fluke. After 1956, when that assessment began to seem prescient, he endured 20 years of emotional, artistic and physical decline, eventually dying of cancer in 1977.

He learned concealment at an early age from his distant father, an incorrigible womanizer whose promising diplomatic career was abruptly terminated after a fling with the future queen of Greece. Although Frank Rattigan lived the rest of his life on a small pension, he played the role of a distinguished elder statesman while continuing to deceive his wife with a series of young blondes.

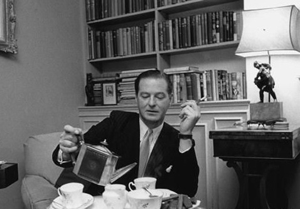

Young Terence detested his father's infidelities, but kept his own counsel. He knew how to maintain appearances - a skill essential to his personal life, for he was a homosexual in a land where homosexuality was a serious crime. His colleagues in the theater (some of them, anyway) were aware of his sexuality, but he was at pains to keep it secret from the public and his parents. None of his several long-term lovers ever was allowed to share a flat with him, although they might live in the same building. homosexual in a land where homosexuality was a serious crime. His colleagues in the theater (some of them, anyway) were aware of his sexuality, but he was at pains to keep it secret from the public and his parents. None of his several long-term lovers ever was allowed to share a flat with him, although they might live in the same building.

Clearly, this reticence had deeper roots than fear of the law; it stemmed from a deep-seated aversion to emotional engagement. ''Behind the apparently carefree mask lived a man crying out to be loved and appreciated,'' writes Wansell, ''but a man who was also incapable of demonstrating that need.''

In the end, the man in the mask at least partly defeats his biographer, for while Wansell exhaustively chronicles Rattigan's professional life, little sense of the man himself emerges from these 434 pages. Aside from a few snippets, Rattigan's life beyond the theater is more or less a blank.

Since Rattigan apparently wrote no diaries or journals, there's some justification for this facelessness as it pertains to his thoughts and feelings. What's more surprising is how little we see of the public man, the Mayfair bon vivant, the man often described as a ''wit'' whose wit is virtually absent from his biography. Surely there are still-living friends and colleagues who might have filled in this part of the portrait, but Wansell has not recorded their recollections.

Most likely, he simply wasn't interested. Because his avowed intention in ''Terence Rattigan'' is to rehabilitate his subject's reputation, his main concern is the work rather than the life, except as the life illuminates the work. Wansell not only makes an impassioned case for Rattigan as an unjustly neglected figure, but he also marshals some impressive support - including, somewhat surprisingly, another master of indirection named Harold Pinter.

It's quite possible that Wansell overstates his case, particularly when he accuses the London critics of virtually killing Rattigan with their dismissal of his later work. But when it comes to the plays themselves, who among us is prepared to argue with him? Even in his palmiest days, Rattigan found little popularity in America; his longest Broadway run was 451 performances of ''O Mistress Mine,'' largely because it starred the popular Alfred Lunt and Lynn Fontanne.

The collected plays are out of print here, and any U.S. theater manager announcing a revival of ''The Winslow Boy'' or ''The Browning Version'' would be considered certifiable. On the other hand (Rattigan might have appreciated the irony, but probably not), so might an impresario who wanted to revive ''Look Back in Anger.'' Theatrical fashion is a stern mistress, and contrarians are few.

In recent years, however, the West End has seen a boomlet of Rattigan revivals - ''The Deep Blue Sea'' and ''Separate Tables'' had nice runs - so it's not inconceivable that some enterprising American will follow suit. In a world where clamor is no longer prized for its own sake, Terence Rattigan might seem more contemporary than we think.

|

![]()